Read the Full Series

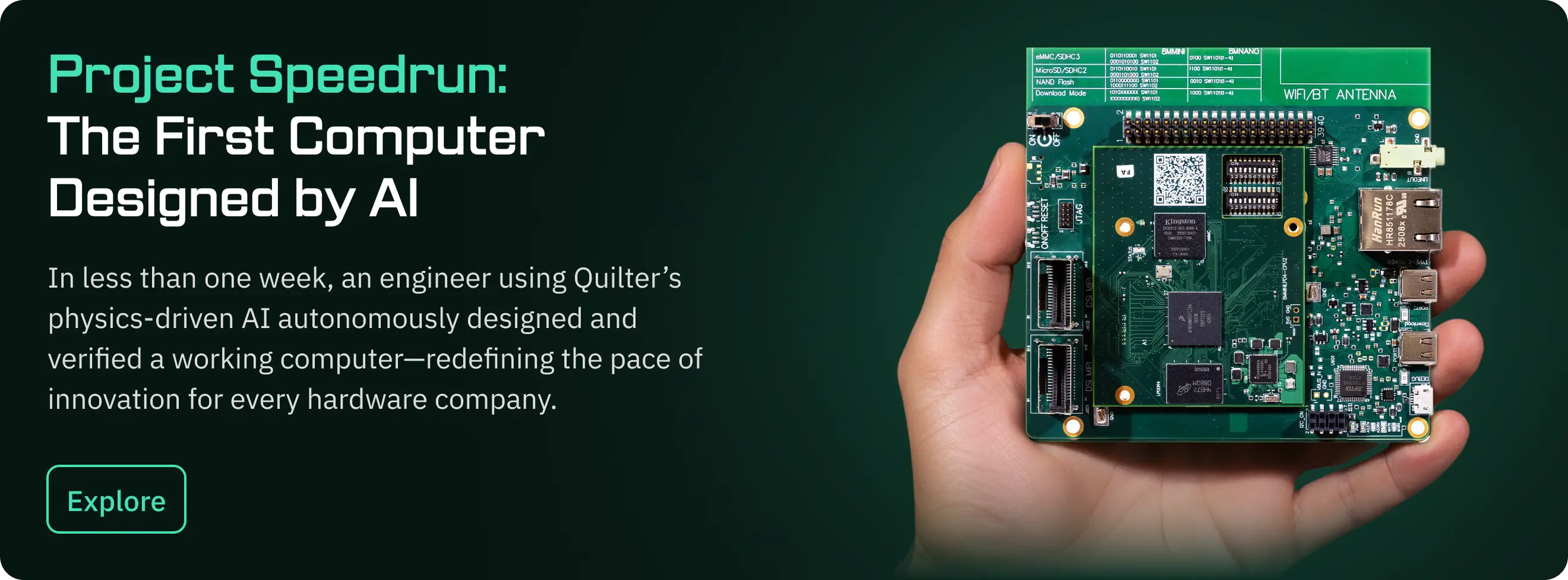

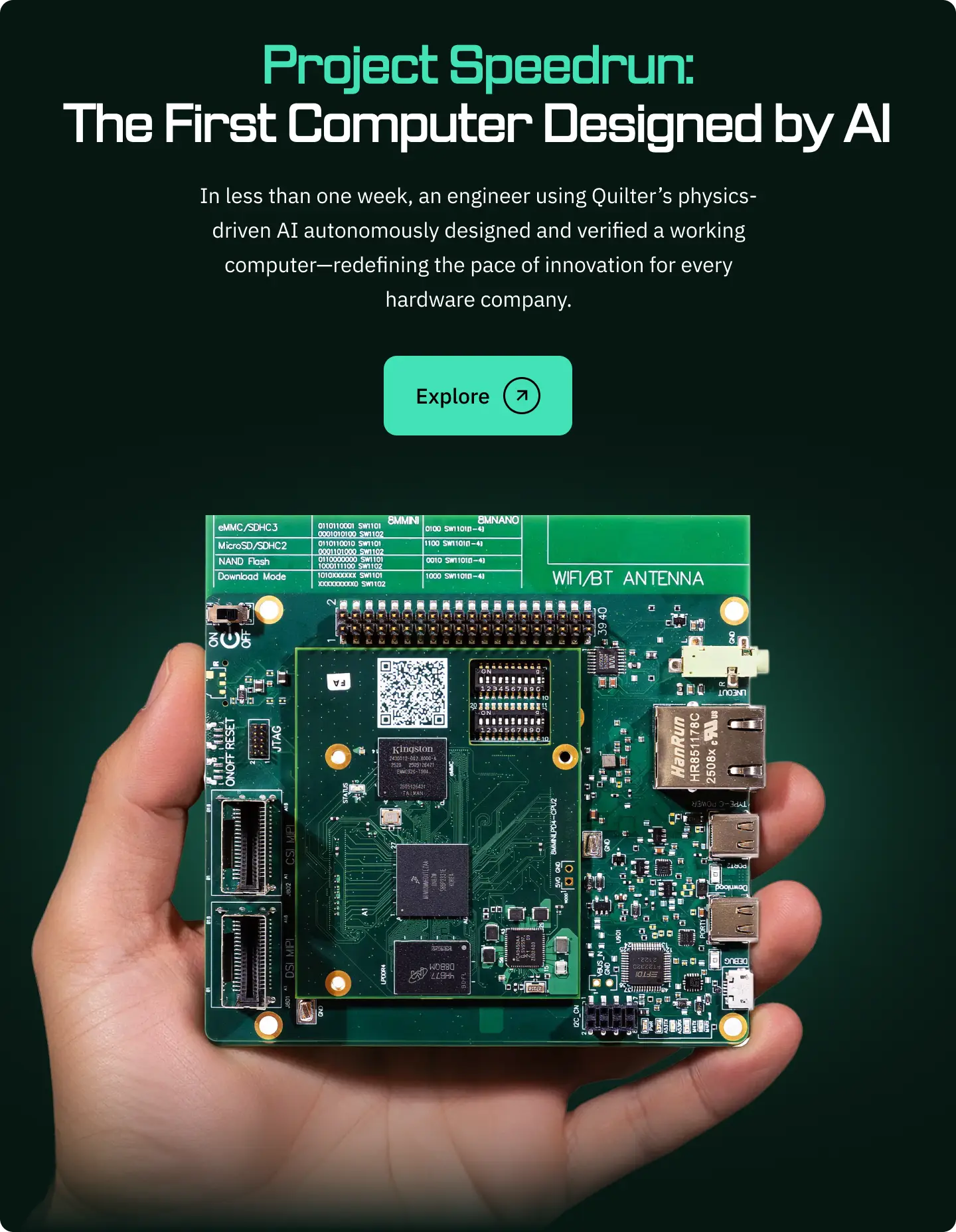

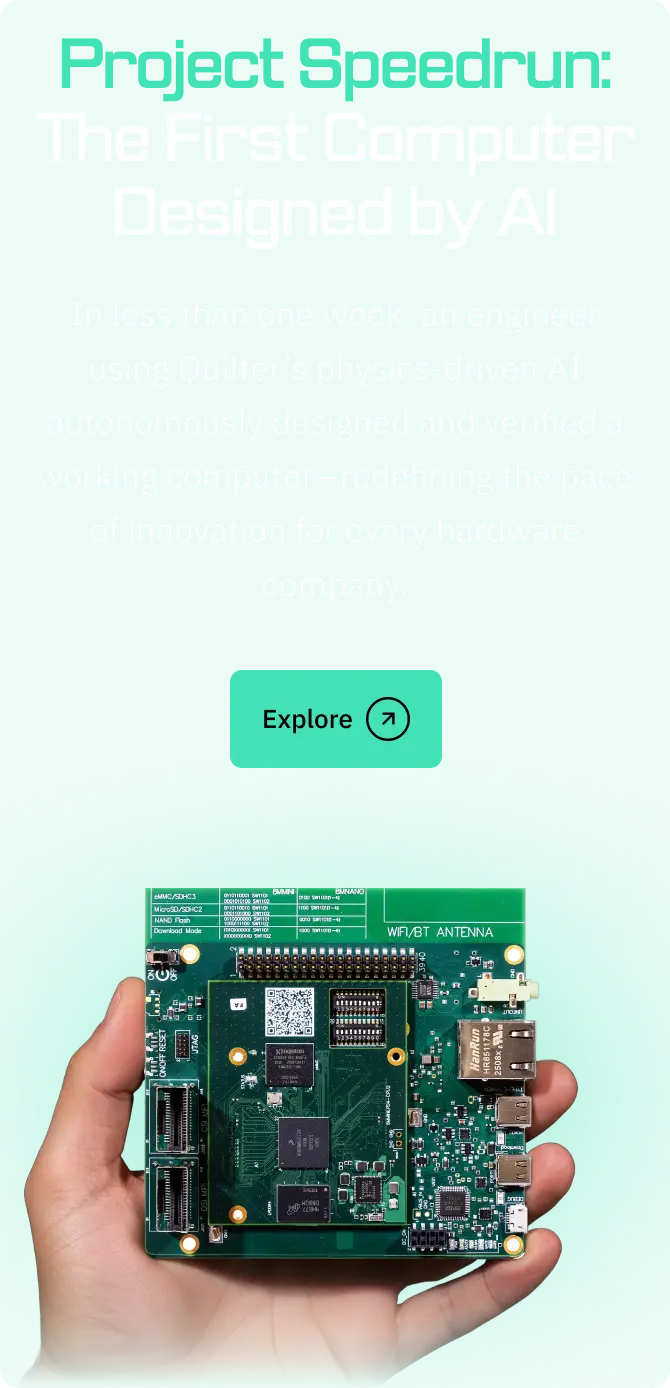

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

Project Speedrun is our challenge to design a complete computer using our physics-driven AI as quickly as possible. This blog series documents how that system was developed and the engineering decisions behind it. Start with the Project Speedrun overview and its results.

We chose this platform because a computer that boots Linux, drives high-speed memory, streams video, and handles mixed-signal subsystems exercises the full stack of placement, routing, PDN, and interface rules. The i.MX 8M Mini platform contains 843 components and 5,141 pins, making it representative of the boards used in production aerospace, automotive, and industrial environments. Professional layout estimates came back at 238 hours for the baseboard and 190 hours for the SOM. Using Quilter, cleanup required only 12 hours on the baseboard and 26.5 hours on the SOM.

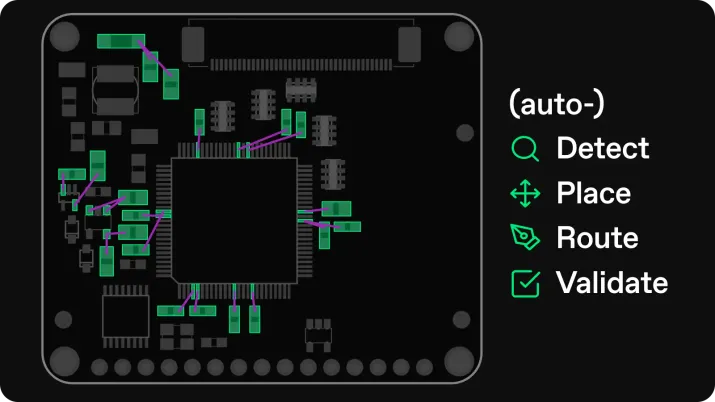

In traditional workflows, handoff from schematic to layout begins with a meeting between the engineer and the PCB layout specialist to clarify intent. Quilter follows the same conceptual structure but replaces that meeting with a process we call circuit comprehension. You upload the project files, verify how Quilter interprets bypass caps, differential pairs, power nets, and special constraints, and then submit the job.

From there, engineers move on to another task while the layout runs unattended, converting those rules into manufacturable geometry.

What follows is how the handoff between Quilter and the engineer works.

Uploading to Quilter (Circuit Comprehension)

Quilter can read the Altium project natively, so all that was needed was to drag-and-drop: we uploaded the project files into Quilter’s interface. From there, the system began interpreting the design for physics-driven layout.

.webp)

We then stepped through the set of critical concerns Quilter is responsible for:

.webp)

Bypass capacitors

Quilter largely auto-detects bypass caps based on their pattern in the schematic (explicitly connected between a component pin and ground). Even so, we reviewed the detected list to catch any misclassifications and ensure all high-frequency decoupling caps were correctly identified.

.webp)

Differential pairs

Differential pairs are automatically detected from net naming conventions (e.g., _P / _N suffixes). We confirmed the pairings and set impedance targets for each group, so Quilter could maintain the required geometry and spacing during routing.

.webp)

High-current nets and polygons

We marked high-current nets explicitly and enabled polygon generation for those nets. This guided Quilter to generate power copper in the right places and to treat those regions with appropriate clearance and width.

.webp)

Special-case components

Certain parts—such as crystals and switching converters—require specific placement and routing practices. We flagged these regions so that Quilter would respect the constraints around them and preserve the intent of the original design.

This review step is the “conversation” that would typically occur between the engineer and the PCB layout specialist. Once we were satisfied with how Quilter understood the design, we submitted the job.

Stack-up Definition

Quilter can determine a stack-up automatically by exploring candidate layer stacks and materials from different manufacturers. For some projects, that’s convenient and sufficient. For complex HDI designs like the i.MX 8M Mini, teams often prefer to specify the stack-up explicitly.

.webp)

For Project Speedrun, we chose to partner with Sierra Circuits and align the design with their fast-turn HDI capabilities. That meant:

- Defining an 8-layer HDI stack-up appropriate for the SOM’s BGA breakouts and high-speed memory.

- Using 2 mil trace/space for the SOM and 3.5 mil trace/space for the baseboard to match real fabrication limits.

- Ensuring the dielectric structure and copper weights supported both signal integrity and power delivery.

We configured the board stack in Altium to match Sierra’s materials and process constraints. Quilter then used this stack-up during routing and physics checks, so every candidate it produced was grounded in what could actually be fabricated quickly by a real vendor.

Baseboard Run

For the baseboard, Quilter generated several candidate layouts that satisfied our constraints and selected stack-up.

The candidate we ultimately built took about 27 hours of compute time, including placement and routing. In that run, Quilter:

- Placed a bit over 500 components, respecting all fixed placements and room-level floorplanning.

- Routed roughly 2,000 pins, achieving 98.4% completion while honoring a 3.5 mil trace/space rule.

.webp)

Perhaps surprisingly, the layout with the highest routing completion was not the one we selected. Quilter also produced a candidate with roughly 99% completion at 3 mil trace/space. That design would have been manufacturable with Sierra and other similarly aggressive fabs, but our goal for this project was to stay within the capabilities of broadly accessible, even low-cost manufacturers you might already be using.

We therefore chose the candidate that balanced:

- High completion rate (98.4%).

- A more conservative 3.5 mil trace/space, manufacturable at fabs such as JLCPCB.

Quilter can explore a range of candidates across the constraint space, and engineers select the one that best aligns with real-world process, cost, and risk.

SOM Run

The SOM posed a much harder challenge than the baseboard. It concentrates the highest-density routing, the i.MX 8M Mini BGA, LPDDR4, eMMC, and other critical high-speed signals into a compact HDI board. It also consumed the majority of our development time during this project.

To make the problem more manageable, we simplified the SOM task for Quilter:

- Human-defined placement

We chose not to use Quilter for component placement on the SOM. Instead, we fixed the placement based on the original design so that we could focus the experiment on routing performance and constraint handling. - Pre-routed BGA fanout

We created a partial human fanout for the BGAs, handling the most delicate escape routing by hand. That allowed Quilter to focus its effort on the remaining difficult work: dense signal routing, length matching, power polygons, and constraint-driven cleanup.

With those simplifications in place, we ran SOM compilations nightly, iterating on Quilter’s algorithms as we learned from each result, driving Quilter development forward. We also decided to remove the WiFi / Bluetooth module as it was out of stock, we didn’t want to risk a major modification to the schematic, and were having enough fun with the rest of the board as it is.

.webp)

Early runs were not yielding the results we needed to be successful in this project:

- 60–70% routing completion.

- No length matching.

- Polygons and high-current nets missing.

- Most differential pairs failing to route.

Over time, as we improved Quilter’s handling of constraints and geometry, completion rates increased, and the quality of the layouts improved substantially.

.webp)

Eventually, Quilter advanced enough that we could reach a DRC-clean layout at 98.7% routing completion at 2 mil trace/space in a job that ran for 15 hours.

The original human design reached about 3.2 mil; we did not fully match that tolerance, but, by leaning on Sierra Circuits’ ability to etch down to 2 mil trace/space that was sufficient for us to release the SOM to fabrication and move forward with the experiment.

Choosing Candidates

Across both the baseboard and SOM, we didn’t select the mathematically “best” candidate based solely on completion percentage.

Instead, candidate selection reflected the same considerations a human layout engineer would apply:

- Manufacturability — choosing 3.5 mil over 3 mil on the baseboard to keep the design compatible with a wide range of fabs.

- Risk and margin — leaning on 2 mil trace/space on the SOM when it simplified routing and stayed within Sierra’s proven HDI process.

Quilter’s role in this phase is to explore the space of possible layouts under the constraints you specify; the engineer’s role is to select the candidate that best balances completion, margin, manufacturability, and risk for the specific project.

A Designer’s Handoff, Without the Wait

Submitting a design to Quilter is straightforward: prepare the project, upload the files, confirm how the system understands constraints, and start the run. The process feels similar to working with a professional layout engineer, minus the dependency on specialist availability, calendar delays, or long feedback cycles. Circuit comprehension ensures Quilter respects design intent, while autonomy delivers results in hours, not weeks. Next, the engineer comes back into the loop to apply the finishing touches that turn a strong automated result into a production-ready design.

.webp)