Read the Full Series

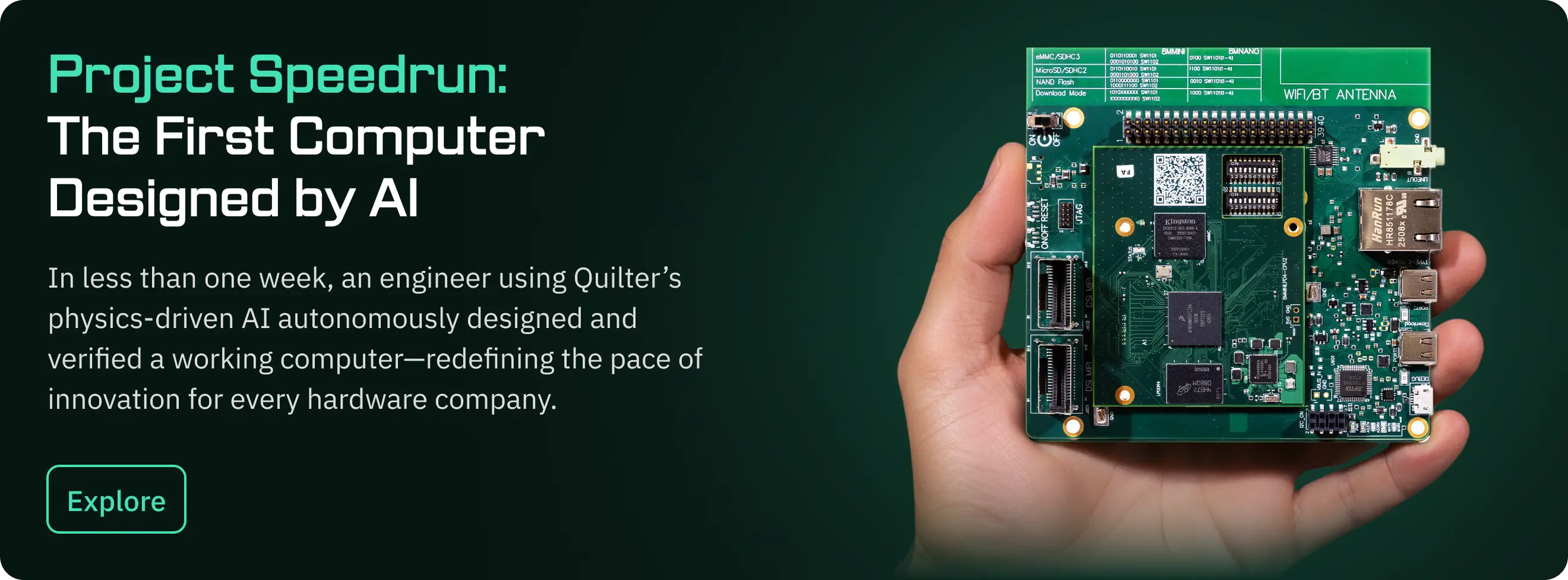

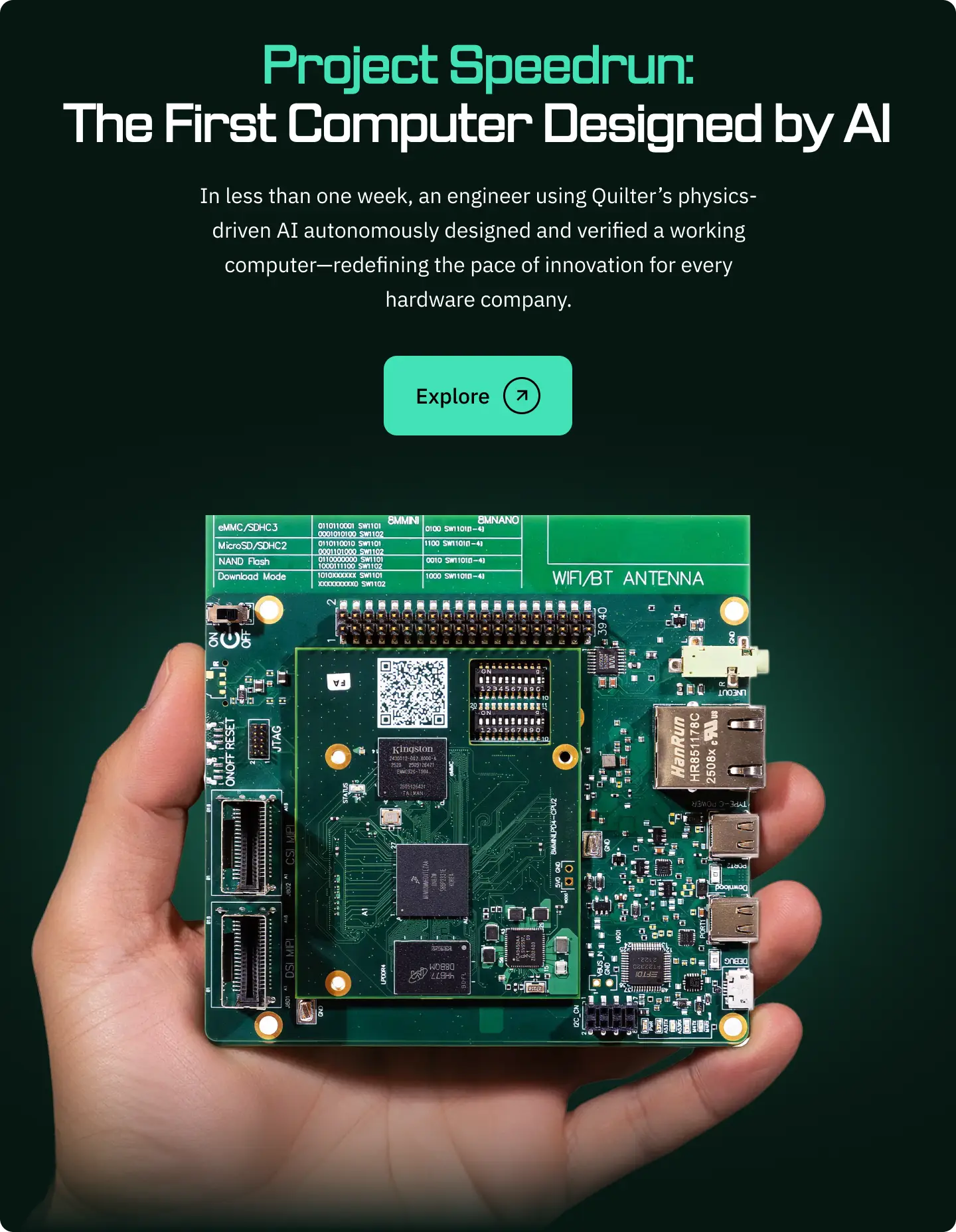

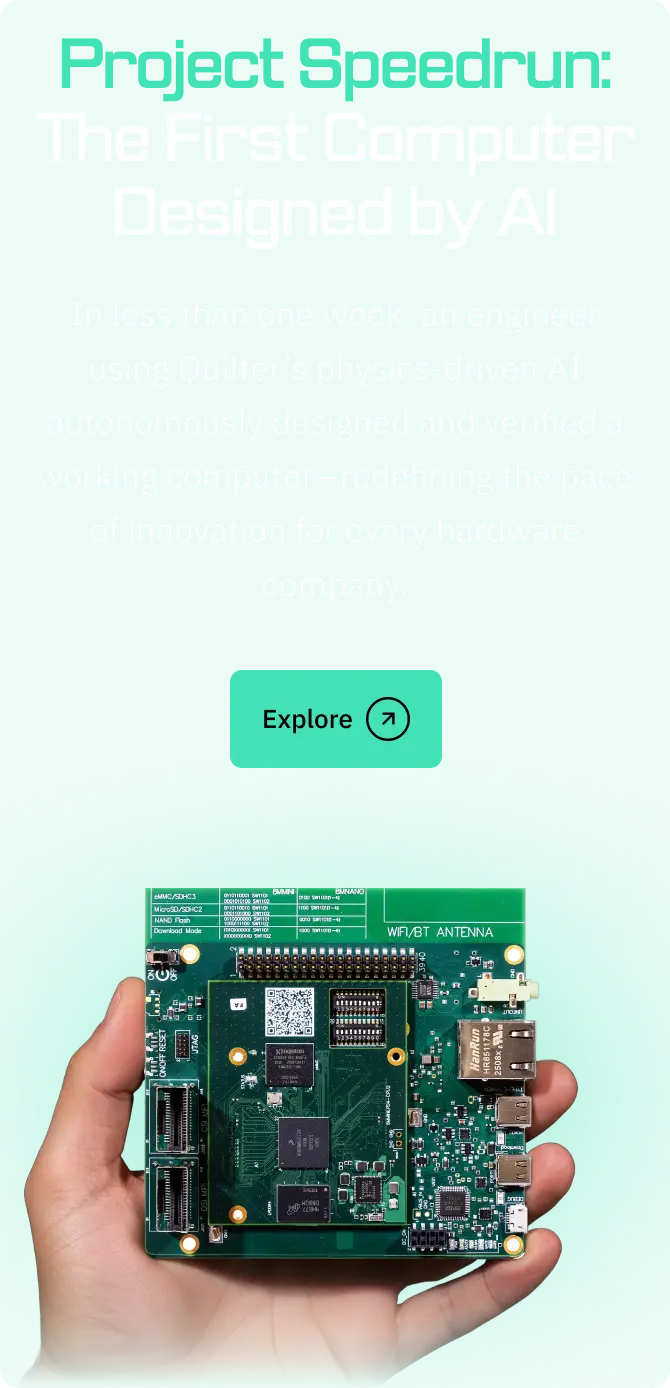

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

Project Speedrun is our challenge to design a complete computer using our physics-driven AI as quickly as possible. This blog series documents how that system was developed and the engineering decisions behind it. Start with the Project Speedrun overview and its results.

We chose a full embedded computer because it evaluates every part of a layout tool to prove itself under real engineering pressures. A system that boots Linux, drives LPDDR4, renders graphics, and handles audio and camera interfaces reveals whether routing, impedance control, PDN, and high-speed behavior are acceptable. Rebuilding the i.MX 8M Mini SOM and baseboard in this context allowed us to measure how much of the workload Quilter could automate. Against a baseline estimate of 238 hours for the baseboard and 190 hours for the SOM, the design reached completion through 27 hours of automated layout and just 12 hours of cleanup for the baseboard and 26.5 for the SOM.

Cleanup is where engineers make the final adjustments that determines whether a board is ready for fabrication. In a manual flow, that step is small because the human already performed hundreds of hours of routing. With Quilter, the AI handles the bulk of the layout, and engineers focus on high-impact refinements.

What Cleanup Means in This Context

Cleanup is not a rescue operation. The boards that Quilter generated were already highly complete and DRC-clean; cleanup was a precision pass to align the design with the engineering team’s expectations, comfort margins, and power-integrity preferences.

Most cleanup tasks fell into a few categories:

- Polygon pours

Quilter can generate power polygons, but for this project the team wanted larger copper regions for comfort. Enlarging polygons often required freeing routing channels, which triggered additional micro-moves and refinements. - Length tuning

Length tuning consumed a significant portion of cleanup time. The biggest reason was that Quilter’s length-tuning engine (at the time) did not yet account for via delay. Once vias were factored in, propagation delay increased, and length tuning needed to be re-adjusted manually. Adding a via-aware delay model to Quilter’s length-tuning engine is a known future improvement. - High-current and power nets

These nets required hand adjustments where the engineers wanted wider pours or more conservative geometries than Quilter had chosen. The goal was to match human comfort levels for power-distribution robustness.

Not a rescue operation, but instead a level of polish that keeps engineers in control and gives everyone peace of mind.

Baseboard 12 Hours of Cleanup Replaced 238 Hours of Manual Routing (Nearly 20x Improvement)

The baseboard cleanup required just 12 hours of engineering time, compared to the 238 hours estimated for a full manual layout. Most of the work focused on a handful of targeted component moves and copper refinements that cascaded through several routing layers.

While the list of edited components appears long, changes primarily involved small adjustments to component placement and copper areas. For example, moving the L102 inductor to sit directly adjacent to its DC-DC converter required shifting several neighboring components to restore clearance and routing channels.

Layer-by-layer comparisons clearly show the difference:

- The Quilter output on the left

- The cleaned-up version on the right

Across layers, the result is not a wholesale redesign but a tightening of polygons, straightening of routes, and small-scale adjustments for electrical and aesthetic cleanliness.

SOM: 26.5 Hours of Cleanup Replaced 190 Hours of Manual Routing (>7x Improvement)

Cleanup on the SOM required 26.5 hours—substantially more than the baseboard, but still only a fraction of the 190 hours quoted for a manual layout.

This aligns with the SOM’s complexity: dense routing, LPDDR4 interface, eMMC, high-speed signals, and tight HDI constraints.

Key cleanup areas included:

- Length tuning with via delay accounted for

Once via delays were included, several tuned routes no longer met their targets. The team re-balanced these nets manually. - Power polygons

Engineers preferred larger polygons for power distribution than Quilter originally produced. Enlarging these pours required opening space, shifting traces, and re-routing small regions to accommodate the changes.

Layer-by-layer comparisons clearly show the difference:

- The Quilter output on the left

- The cleaned-up version on the right

As with the baseboard, these edits did not require major structural changes. The SOM layout remained fundamentally the output of Quilter; cleanup refined the copper and adjusted a subset of components to align with engineering preferences and power-integrity considerations.

The Work That Remains Is Small—And the Time Savings Are Large

It’s easy to interpret cleanup as a sign of failure, but that interpretation ignores the scale of savings. The comparison is not “cleanup vs. no cleanup”—it’s 38.5 hours vs. 428 hours. Cleanup is a small amount of targeted work that replaces months of manual routing.

Instead of spending hundreds of hours routing by hand, engineers start with a nearly complete, constraint-respecting layout and focus only on targeted refinements.

On the baseboard, a 12-hour cleanup replaced an estimated 238 hours of manual routing. Some boards compress modestly, while others compress by an order of magnitude.

Taken together, 38.5 hours of cleanup after just 27 hours of autonomous runtime instead of 428 hours of manual effort—compressing a timeline from one quarter to one week.

.webp)