Read the Full Series

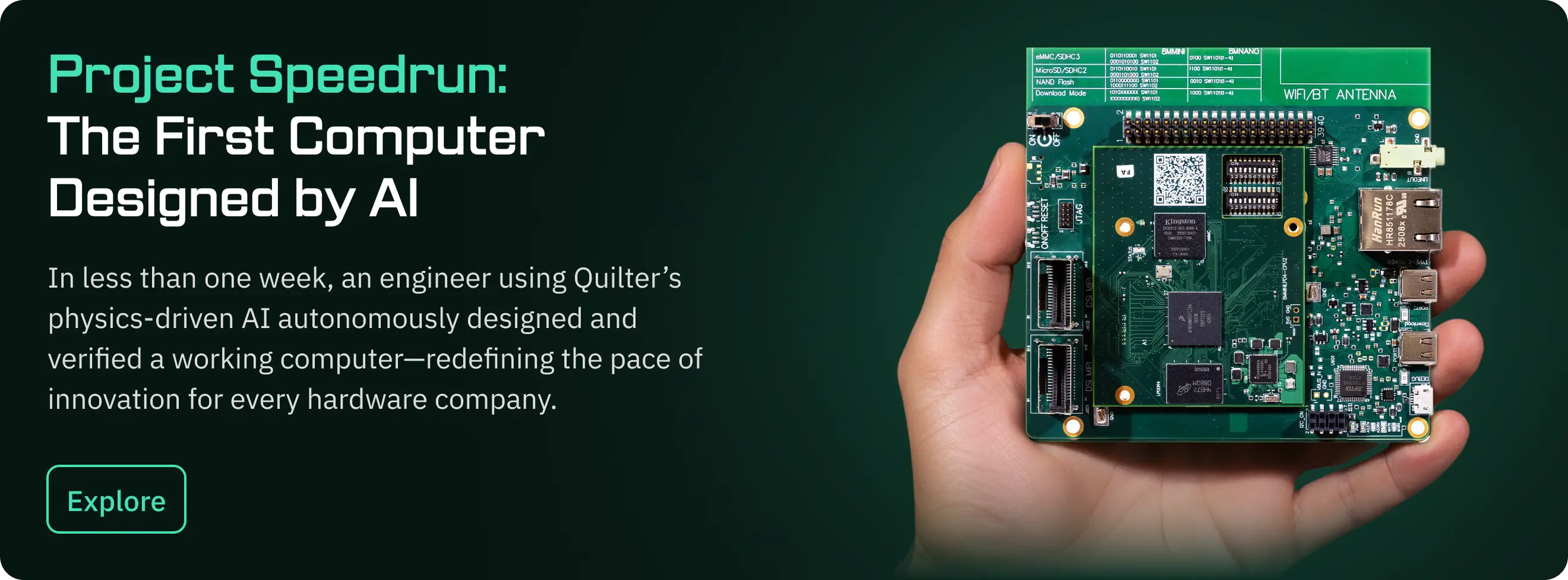

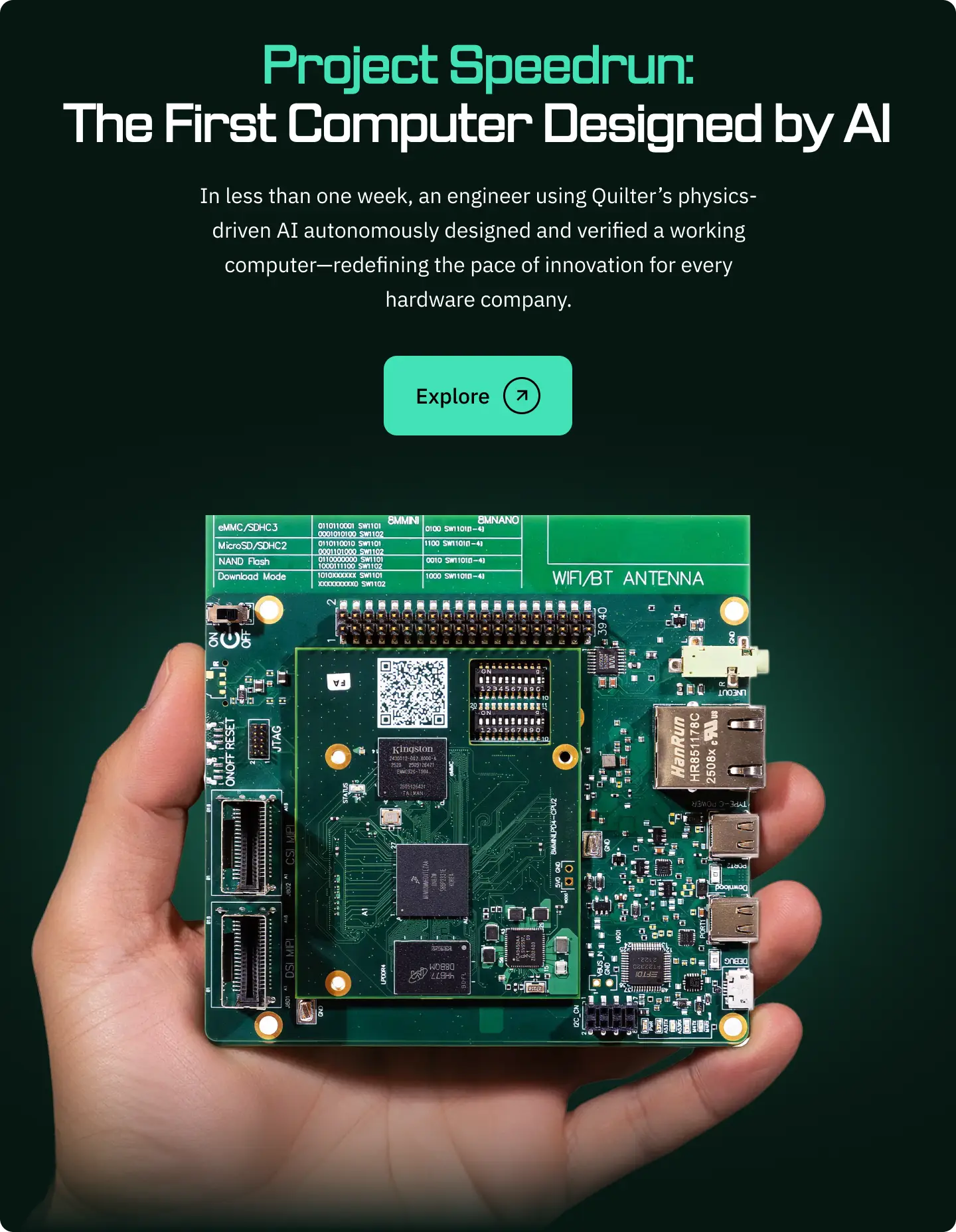

This article is one part of a walkthrough detailing how we recreated an NXP i.MX 8M Mini–based computer using Quilter’s physics-driven layout automation.

Jarvis Autey’s path to software engineering wasn’t linear. “I did civil engineering as my undergrad,” he said, “and during my masters we were doing computer vision for tracking vehicles for traffic safety.” That project lit a spark. Programming, once peripheral to his field, became the throughline of his career.

Now at Quilter, Jarvis applies a lifetime of solving tangible, physical problems to the digital design frontier. His story captures the spirit of “Humans in the Loop”: engineers who move fluidly between worlds like bridging code and concrete, geometry and imagination, structure and software.

Origins

For Jarvis, software engineering has always been about translating structure in the real-world to code. “I started doing programming for engineering purposes,” he said, “and every job I took I was trying to do more programming to solve engineering problems.” His early projects wove together computation and the physical world—from writing software for geotechnical equipment to CAD automation for architectural engineering.

The work allowed him to apply his more traditional engineering background: “Writing code for engineering applications requires first learning enough about the field's methods to be able to translate them into code.”

Journeys in Engineering

Jarvis has a largely mobile career path: while working on structural engineering CAD automation, he had the opportunity to work as a contractor for Tesla’s manufacturing team which he took with a confident, “Yeah, I can figure out how to do this.” He then went on to apply his software skills for manufacturing data automation, and was fortunate to be a part of Model 3’s early manufacturing map. After this, he joined many former team members at CloudKitchens on a newly-formed Hardware Engineering team where he worked on interesting technology for commercial kitchens operations as well as order handling.

Those experiences built the foundation for the kind of systems thinking he brings to Quilter: breaking through complex, and highly technical ecosystems to make things work together often without a map.

Why Quilter?

When Quilter’s founder began expanding the team, Jarvis saw an opportunity to connect his interdisciplinary experience with an equally hybrid mission. “At that point most engineers at Quilter were specialized in fields like Computational Geometry and Machine Learning. We were rebuilding the web app for open-beta. I believed I could help bridge scientific and application code.”

At Quilter, Jarvis has worked worked on server-side development, and also extensively on File I/O.: “reading and writing from different CAD software file structures… KiCAD, Altium, Cadence, now Xpedition.” The job requires reverse-engineering each system, importing and exporting their data to fit within Quilter’s compiler. “"Some file types are just large binary files without any documentation" he explained, "It's a significant challenge.”

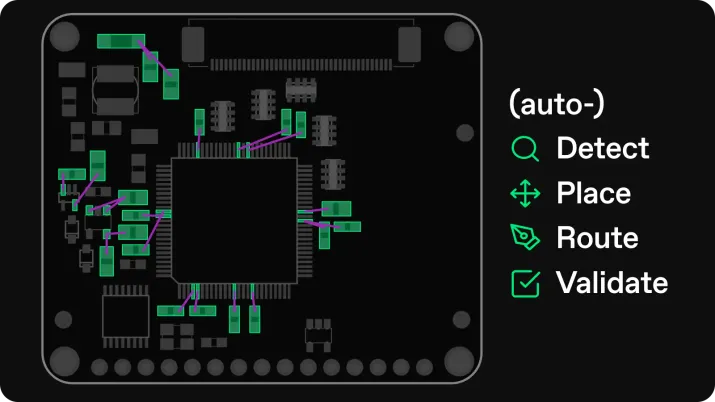

Even amid that complexity, Jarvis’s long-term interest lies in circuit comprehension: “Code that is able to identify concepts without using really rigorous rules.” His goal? To help machines recognize circuits the way an electrical engineer would both conceptually and logically.

Beyond the Workbench

He appreciates the company’s small-team culture. "We have a pretty flat structure at Quilter. Engineers take ownership of their team’s domain, but also contribute their expertise across teams."

A Line to Remember

"Circuit boards are physical, real-world devices. If the results of our algorithms don't produce working products, we have not understood and modeled the requirements properly."

Closing Note

Jarvis’s story embodies the kind of grounded brilliance that makes Quilter’s mission possible: practical, patient, and curious. In every line of code and every tough corner case, he’s bridging the digital and the physical, teaching machines how to see the logic engineers already understand.